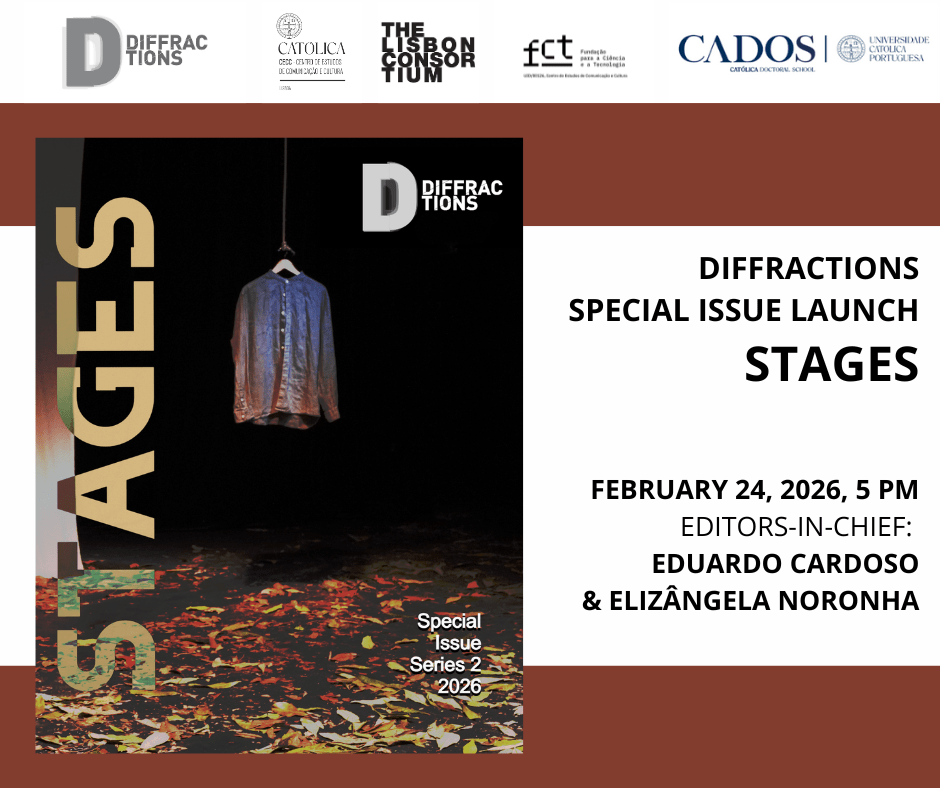

The launch of Diffractions special issue “Stages”, on ageing, communication and culture, takes place 24 February at 17:00 in Room Expansão Missionária. The editors and CECC members Eduardo Prado Cardoso and Elizângela Carvalho Noronha will discuss how this collection of articles that advance the discussion of ageing interconnected with various fields, such as communication, dance, theatre, and literature.

Learn more about Diffractions: https://revistas.ucp.pt/index.php/diffractions/

Category: Diffractions

-

Launch of Diffractions special issue “Stages”, 24 Feb 17:00

-

Launch | Diffractions: “You are what you eat”: On food, culture(s) and identities

On 9 December, Federico Bossone, the Editor-in-Chief of the latest issue of Diffractions, introduced the contents of No. 10, “You are what you eat”: On food, culture(s) and identities.

This issues considers the complex relationship between food, identity and culture. As Bossone points out, “food is not a neutral or purely sensory object but a powerful cultural medium—capable of negotiating and renegotiating heritage, contesting belonging, and acting as a means for humankind to perform status and shared ideologies […]. Its value lies in being a bearer of memories and a marker of identities. Whether examined through aesthetic practice, historical transformation, migratory flows, or ideological frameworks, food culture explores the tensions between the personal and collective, the local and global, the traditional and the innovative.” (2025, 1) The issue sets a diverse intellectual table including food memories, practices, and the ethics and politics of food, through the reflection by 9 international scholars and the artwork “Patuá: Where Portugal Meets Macau” by Eduardo Melo.

We invite you to get to know the latest issue here.

-

Launch | Diffractions: “”You are what you eat”: On food, culture(s), and identities

The launch of No. 10 of Diffractions: “You are what you eat”: On food, culture(s), and identity, edited by Federico Bossone (PhD in Culture Studies) takes place 9 December at 17:00 in Room 421 (Library building).

Diffractions is an online, peer-reviewed, open-access graduate journal for the study of culture. It is published bi-annually under the editorial direction of students from The Lisbon Consortium’s doctoral programme in Culture Studies with support from CECC.

https://revistas.ucp.pt/index.php/diffractions/

-

CfP | Diffractions: Speak at Your Own Risk: The Many Faces of (Self-)Censorship

The Call for Papers for issue 12 of Diffractions is out!

CALL FOR PAPERS

Speak at Your Own Risk: The Many Faces of (Self-)Censorship

Editors-in-chief: Inês Fernandes and Teresa Weinholtz

Deadline for abstracts: November 15, 2025

“In a society like ours, the procedures of exclusion are well known. […] We know quite well that we do not have the right to say everything” (Foucault 1980, 52). Often regarded as an instrument of repression of ideas and information (American Library Association 2021), censorship “refers to the control by public authorities (usually the Church or the State) of any form of publication or broadcast, usually through a mechanism for scrutinising all material prior to publication” (McQuail and Deuze 2020, 589). Most commonly associated with control that is visible and imposed by the State, censorship can be regarded “as a subject of history, which means that it has to be considered not only in its formal dimension, as an apparatus of State control and repression, but also as a social agent that permanently and complexly shapes the relationship between individuals and institutions” (Barros 2022, 17). Either through literature, with the act of burning books in Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 ([1953] 2018) and the control of thought in Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four ([1949] 2023), or the morality or political restrictions in cinema (Biltereyst and Winkel 2013), or even contemporary China with the firewall that controls internet access (Stanford University n.d.; Gosztonyi 2023), censorship has gathered a broader definition beyond that of State control.

The study of censorship should not be limited to dictatorships or historically oppressive political regimes, as it can also be found as an institutionalised social force, based on the concept of “public morality” (Mathiesen 2008, 577), in cultural institutions, digital platforms, and academic environments. In its more formal configuration, censorship can be a tool of repression and strict prohibition. In its informal and more personal perspective, it can be viewed as socially imposed censorship and/or self-censorship, thereby expanding its definition “to the productive force that creates new forms of discourse, new forms of communication, and new models of communication” (Bunn 2015, 26). As Judith Butler (2021) argues, censorship precedes speech, as it determines in advance what type of speech is or is not acceptable. Similarly, Bourdieu (1991) describes how censorship affects language, as what we are authorised to say becomes internalised. Censorship, in this light, is not only a legal or institutional force, but can also become a social imposition. This issue thus seeks to explore the many forms of censorship, self-censorship, and everything in between; past and present, imposed and chosen, visible and hidden.

Recent events have shed light into an ongoing reality of censorship that contributes to the urgency of these discussions. Most recently, in the United States, governmental restrictions on words such as “women,” “diversity,” and “disability” in academic grant applications and school curricula (Yourish et al. 2025) reveal the close relationship between language and ideological control through State censorship. In Germany, artists and curators have been fired or publicly blacklisted for expressing solidarity with Palestine on their personal social media (Solomon 2023), demonstrating that speech can be punished even within liberal democracies when it contradicts socially established narratives, creating environments of fear through instances of social censorship. On social media platforms like TikTok, users increasingly engage in linguistic innovation. With phrases like “unalive” instead of “kill,” they intentionally alter or misspell specific trigger words to avoid algorithmic suppression, or shadowbanning (Calhoun and Fawcett 2023). This form of self-censorship is strategic and creative, but also reveals the pressures users face to remain visible in social media spaces that are moderated by strict automated systems.

This issue invites contributions that critically examine how all forms of censorship and self-censorship operate today, as well as how they have operated historically. We invite interventions from different contemporary, historical, and geopolitical perspectives, and interdisciplinary approaches from all fields in the humanities. Besides proposals for academic papers on the topic of this issue, we also welcome proposals in the form of interviews, book reviews, essays, artistic contributions, as well as non-thematic articles. Suggested topics include, but are not limited to the following:

- Historical and contemporary (self-)censorship

- Censorship and political regimes

- Self-censorship as personal, professional, and intellectual preservation

- Censorship and self-censorship…

- in media ecosystems

- in film and cinema

- in art, performance, and curatorship

- in image and photography

- in language, literature, and translation

- in knowledge and academia

- in artificial intelligence

- in memory: preservation and/or erasure

- in children’s media and literature

- in social media, online content and behaviour

- and cancel culture

- …

For artistic submissions, we are interested in proposals that engage in form or content with the theme of censorship and/or self-censorship, such as:

- Visual essays

- Graphic or visual storytelling

- Collaborations between text-based and image-based artists

- Poetry and visual poetry

- …

Submissions and review process

Abstracts will be received and reviewed by the Diffractions editorial board who will decide on the pertinence of proposals for the upcoming issue. After submission, we will get in touch with the authors of accepted abstracts in order to invite them to submit a full article. However, this does not imply that these papers will be automatically published. Rather, they will go through a peer-review process that will determine whether papers are publishable with minor or major changes, or they do not fulfil the criteria for publication.

Please send abstracts of 150 to 250 words, and 5–8 keywords by NOVEMBER 15, 2025, to info.diffractions@gmail.com with the subject “Diffractions 12”, followed by your last name.

The full papers should be submitted by MARCH 15, 2026, through the journal’s platform: https://revistas.ucp.pt/index.php/diffractions/about/submissions.

Every issue of Diffractions has a thematic focus but also contains special sections for non-thematic articles. If you are interested in submitting an article that is not related to the topic of this particular issue, please consult the general guidelines available on the Diffractions website at https://revistas.ucp.pt/index.php/diffractions/about/submissions. The submission and review process for non-thematic articles is the same as for the general thematic issue. All research areas of the humanities are welcome, and we accept contributions in English or Portuguese.

You can find the full CfP here.

-

CfP | Diffractions: Visual Poetics and Gender: Rendering Absence and Error

Diffractions – Graduate Journal for the Study of Culture has launched the Call for Papers for Issue 11: Visual Poetics and Gender: Rendering Absence and Error. The deadline for abstracts is May 31, 2025.

Visual Poetics and Gender: Rendering Absence and Error

Editors-in-chief: Emily Marie Passos Duffy and Amadea Kovič

Absences, both as a verbal phenomenon and textual/visual strategy, are evocative. They can convey even more than what is included in a work—pointing to the unsaid, the unexpressed, redacted, or censored. A space, an error, or an errant form can be seen as a collision between semiotic systems, lending itself to ekphrastic consideration, braiding together the verbal and the visual. History until this day is punctuated with gendered absences, and the visual mode has the potential to underscore them by making them visible; as noted by Elisabeth Frost (2016), there are “specifically feminist possibilities of a visually-oriented poetics” (339). Glitch feminism, for example, builds itself on the notion of the ‘glitch-as-error,‘ a term seeping from the digital world to claim and embrace the fluidity of the material against the dominance and normativity of the binary (Russell 2020). This call finds itself at an intersection between visual poetics as an approach/ philosophy and visual poetry as one of its genre outputs, engaging with both the visual and verbal to explore gender and absence.

Visual poetics are defined through a number of perspectives: as an approach described by Mieke Bal (1988), it denies the “word-image” opposition and explores possibilities of a poetics of the visual and the visual dimensions of the written word, calling for mutual collaboration between and across mediums (178), while Frost (2016) defines it “as writing that explores the materiality of word, page, or screen” (339). Within the genre output of visual poetry—a genre umbrella that may include concrete poetry, asemic (“wordless”) poems, choreopoems, erasures, and redactions—there are countless examples of artists working on “visual compositions precisely to question the gendered politics of the history of poetry, material culture, and reading or performance” (Frost 2016, 339).

Within the context of this call, we are specifically interested in the potential of visual poetics to render visibility to absences, engage with error, and convey histories of silence, censorship and erasure. What happens when certain narratives lack visibility, and present blank spaces within public visual language? Works by 21st century women poets Anne Carson and Gabrielle Civil demonstrate a poetic engagement with absence, as well as the material and visual aspects of both language and translation. In a note following “errances: an essay of errors after Jacqueline Beaugé-Rosier,” performance artist, poet, and writer Gabrielle Civil (2020) describes her ongoing work of translating A vol d’ombre by Haitian poet Jacqueline Beaugé-Rosier as “a trial of wandering,” “a shadow lineage” and “a timeline of discarded choices.” The essay´s visual dimensions—namely, white space, brackets, and cross-outs— constitute an archive of doubt, possibility, absence, and trials.

Absences and errors can convey meaning and possibilities for reading and interpretation—in Civil’s case, they indicate a grappling with the language itself, and the challenges translation presents with “false friends, language, meaning, and memory” (Civil 2020). In Carson’s case, the brackets and white space in If Not, Winter: Fragments of Sappho perform and engage with the loss—an elegy for the missing pieces of the source text itself in its entirety, and an engagement with what remains.

This call is interested in how gender-based concerns can be expressed through visual language and its absences, resulting in visual poetics in their varied and multilayered manifestations—and how these intersections may illuminate the bounds and possibilities of genre, form, and semiotic system.

We invite explorations and examples of artistic productions which utilise the interplay between the verbal, visual, and gender—in particular, the use of visual poetics to highlight absence, invisibility and erasure, considering:

- How can visual language be used to convey narratives that are beyond the verbal?

- How might an absence be translated into visual language?

- What is the role of error in visual poetics, and how does it connect to gender?

Proposals for thematic articles in response to this call are welcome, including but not limited to the following topics:

- The translation of visual or concrete poetry

- Visual poetics and gender

- (In)visibility

- Expressions of error in visual poetry

- Visual rendering/annotation of speech-based poetics

- Absence as evocative, absence as resistance strategy

- Ekphrastic writing—writing in response to visual art

- Collaborations between visual artists and poets

- Street art/graffiti as a form of visual poetics

- Intertextuality/Intersemiotic translation and gender

- Visual poetics, AI and technology

- Visual poetics and theory

For artistic submissions, we are interested in the following:

- Visual essays

- Interviews

- Graphic or visual storytelling

- Memes (original or curated with attribution)

- Poetry that engages with erasure or redaction

- Translated poetry with a translator’s note

- Collaborations between text-based and image-based artists

As with thematic articles, the artistic contributions should not exceed the length of 9000 words, in English or Portuguese. With artistic submissions, authors may also include an optional short (150-200 words) synopsis of the work in lieu of an abstract.

Submissions and review process

Abstracts will be received and reviewed by the Diffractions editorial board who will decide on the pertinence of proposals for the upcoming issue. After submission, we will get in touch with the authors of accepted abstracts in order to invite them to submit a full article. However, this does not imply that these papers will be automatically published. Rather, they will go through a peer-review process that will determine whether papers are publishable with minor or major changes, or they do not fulfill the criteria for publication.

Please send abstracts of 150 to 250 words, and 5-8 keywords by May 31st 2025, to info.diffractions@gmail.com with the subject “Diffractions 11”, followed by your last name.

The full papers should be submitted by August 31th 2025, through the journal’s platform: https://revistas.ucp.pt/index.php/diffractions/about/submissions.

Every issue of Diffractions has a thematic focus but also contains special sections for non- thematic articles. If you are interested in submitting an article that is not related to the topic of this particular issue, please consult the general guidelines available at the Diffractions website at https://revistas.ucp.pt/index.php/diffractions/about/submissions. The submission and review process for non-thematic articles is the same as for the general thematic issue. All research areas of the humanities are welcome.

See full call with bibliography here: https://revistas.ucp.pt/index.php/diffractions/announcement

-

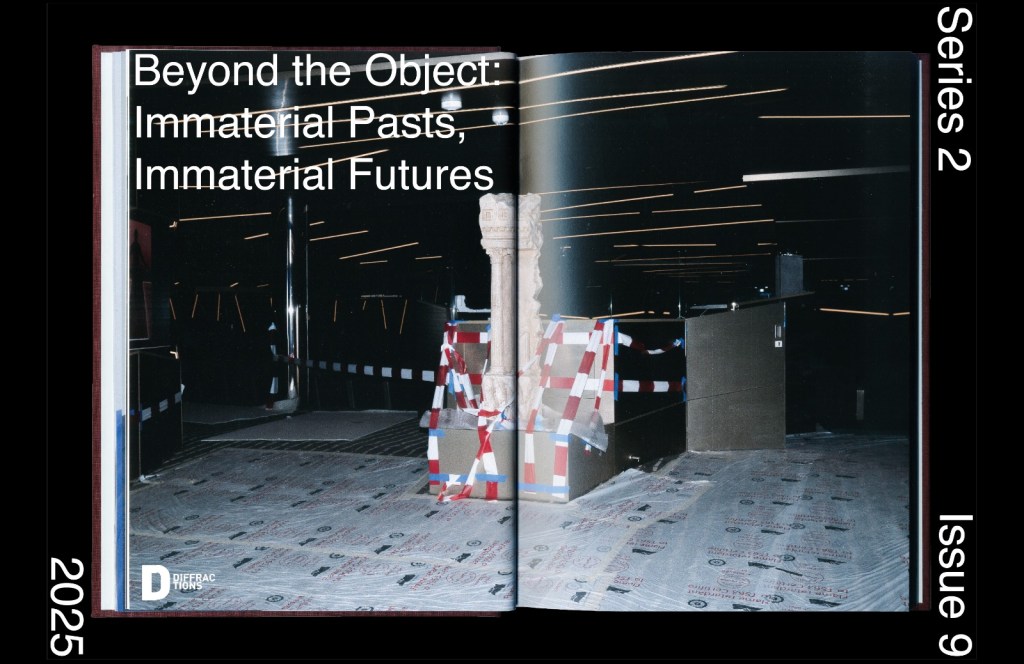

Diffractions | #9 Launch, March 11, 19:00, Hangar

The launch of the latest issue of Diffractions will take place at Hangar (Rua Damasceno Monteiro 12) on March 11, 2025.

The editors Federico Rudari and Teresa Pinheiro will introduce the issue, its themes, and contributions (in Portuguese and English), and a performance by Polido, musician and artist, will follow. The event counts on the support of CECC.

-

Closing of Rita Ravasco’s Tempo Sentido: Creative Writing Workshop and Open Mic at Casa do Comum (Dec. 8)

Nostalgia is a “temporal paradox” (Ravasco 2024) that blurs the lines between past and present, between imagination and remembrance. It can be cathartic, alchemical, dull, inspiring or painful. It can be consciously provoked or accidentally triggered by a vision, a sound, a smell.

For the closing of Rita Ravasco’s installation Tempo Sentido (Casa do Comum, Nov. 13 – Dec. 8) we invite you to participate in our Creative Writing Workshop and/or our Open Mic Session, and share what makes you nostalgic!

Bring an object or photograph, personal or found, and look into how and why it triggers a nostalgic longing in you.

Creative Writing Workshop (Bilingual EN/PT)

Dec. 8, 15h-16h

Through a series of generative writing prompts anchored in the photo or object you decide to bring, we will explore different dimensions of nostalgia and the way it interacts with emotions, public and private life.

The workshop prompts will be offered in English and Portuguese. You are free to write in any language.

Workshop participants have the option to share the outcome of this creative writing session in the Open Mic Session that follows after.

Workshop led by: Emily Marie Passos Duffy (Lisbon-based poet, performer and researcher)

Workshop spaces are limited, if you are interested, please register under: info.diffractions@gmail.comOpen Mic (Bilingual EN/PT)

Dec. 8, 16:30h-18h

In our Open Mic Session, we invite participants to share with us their thoughts, stories, poems, etc. about a nostalgic object or photograph they choose to bring (ca. 5 mins/participant). Photographs can be brought in analogue or digital form. Feel free to speak in Portuguese or English.

-

Diffractions | Vernissage at Casa do Comum, November 13, 5pm

Rita Ravasco’s Tempo Sentido is moving to Casa do Comum from 13 November – 8 December.

Tempo Sentido [Time Sensed] is Ravasco’s multimedia digital and on-site installation, originally developed for the Nostalgia exhibition (Universidade Católica Portuguesa, 2024) as part of the current Diffractions issue 8 on the topic of nostalgia. The work consists of three parts: the digital issue cover in conversation with a video-animation, both accessible online, and the material piece.

In this piece Ravasco figuratively represents the human mind as a sensory archive through a web of interconnected objects, representing the way memory and nostalgia can be triggered by sensory experience, creating an endless network of memory, longing and affect across time and space. The close communication between the digital and the physical mirrors the extension of our own lives and memories into digital space and evokes a myriad of questions connected to the functioning of nostalgia as a felt experience fusing diverse memories, times and spaces in the human mind as it is triggered by the physical and the digital.

The piece has been funded by CECC – The Research Centre for Communication and Culture.

You can find the issue of Diffractions about Nostalgia here: https://revistas.ucp.pt/index.php/diffractions/Curators: Amadea Kovič, Emily Passos Duffy, Miriam Thaler

We hope to see you there!

-

Diffractions: Rita Ravasco’s “Tempo Sentido” in exhibition at FCH

Diffractions, No. 8 (2024): Nostalgia

Guest artist: Rita Ravasco

Edited by:

Miriam Thaler

Gloria Adu-Kankam

João Oliveira

Tempo Sentido“The cover art by Rita Ravasco, showcasing a seemingly random collection of dysfunctional objects connected by colourful threads, is part of a multimedia art piece with the title Tempo Sentido [Time Sensed] exploring the functioning of memory and nostalgia. The human mind is figuratively represented as a sensory archive through these interconnected objects, representing the way memory and nostalgia can be triggered by sensory experience, creating an endless network of memory, longing and affect across time and space. The digital painting on our cover is interconnected with another digital piece, a video-animation, and a temporary on-site installation at Universidade Católica Portuguesa. Our cover art is in fact a digital sketch and image detail of the installation on site and together with the animation will remain as a digitally archived remnant of the on-site installation. The close communication between the digital and the physical mirror the extension of our very own life and of our memories into digital space. The multilayered piece evokes a myriad of questions connected to the functioning of nostalgia as an affect fusing diverse memories, times and spaces in the human mind as it is triggered by the physical and the digital.” (Miriam Thaler, “Editorial: Nostalgia,” Diffractions 8, 2024: 2-3)

https://revistas.ucp.pt/index.php/diffractions/issue/view/887

Rita Ravasco’s Tempo Sentido is in exhibition at Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Faculty of Human Sciences, next to CADOS, until July 26, 2024.

The exhibition is sponsored by CECC – The Research Centre for Communication and Culture.

-

The Inauguration of Deaf Studies Lab and the launch of Diffractions on Deaf Culture

In 4 December, 2023, the CECC organized an informative meeting on its new Deaf Studies Lab that is being developed by The Lisbon Consortium alumna Cristina Gil (CECC-UCP), Joana Pereira (CECC-UCP), Helena Carmo (CIIS-UCP) and Paulo Vaz de Carvalho (CIIS-UCP).

The Deaf Studies Lab results from the work that has been pursued by the first Portuguese researchers with specific, graduated academic training in the field of Deaf Culture, and is transversal to the several research groups and scientific areas to which CECC, the Research Centre for Communication and Culture from Universidade Católica Portuguesa, is dedicated to.

At the same occasion, the latest issue of Diffractions, Deaf Culture, was launched.

Congratulations to the whole team for the the pioneering work in Portugal! -

Launch: Diffractions Issue 7: DEAF CULTURE

The launch of Diffractions #7: DEAF CULTURE, edited by Guest Editors Cristina Gil, Genie Gertz, Joana M. Pereira, and Tom Humphries, will take place on Monday, December 4th, at 7 pm.

The launch will occur as part of the launch of CECC’s new Deaf Studies Lab, which will take place in Sala de Exposições at 5 pm (UCP library building, 2nd floor).

-

Call for Articles: Diffractions Graduate Journal for the Study of Culture

Call for Articles

(Dis-)covering ciphers: objects, voices, bodies.

Deadline for submissions: October 31, 2018

To analyze the ways in which cultural objects acquire meaning can also be understood as looking at the technologies by which those objects have become enciphered. In this issue of Diffractions we aim to look at the concept of the cipher in its myriad ways of appearing, be they cultural, social, political, technological, linguistic or economic in nature.

To give an example of that last category, one merely needs to point towards Marx’s theory on the fetishization of commodities. There, the process through which the material existence of products of labor can become invisible behind their exchange value, is formulated as a process of hiding what is central to the object; its material existence and its use value. In other words, the Marxist theory of fetishization can be understood as the discovery of a cipher, the cipher of exchange value.

But the concept of the cipher travels easily, and can be situated in many locations. In Adriana Cavarero’s work on the voice, she considers the ways in which the bodily aspects that are associated with the vocal are often hidden behind its semiotic, linguistic, and signifying capacities. That is to say, speech functions as a cipher for the materiality of the vocal. The vocal needs to be deciphered.

But what is a cipher? And how to know if we are dealing with a cipher to begin with? The cipher raises questions. In technologico-linguistic terms, a cipher calls for a key. A password. A way to de-cipher what was first en-ciphered. Perhaps a text that appears as a cipher is a plain text after all. The cipher’s call is not always obvious. Ciphers can conceal their act of concealing; hide not only what they are hiding, but that they are hiding as well; steganography.

Ciphers cut. And, as Jacques Derrida writes, they produce an inside and an outside, insides and outsides. In order to protect what is behind the cipher, the cipher has to function as a passageway, letting some through while excluding others. In order to be allowed to enter, something must already be known. The cipher marks the limits of something hidden. But some measure of knowledge is nevertheless presupposed. It marks the boundaries of a relationship. It conceals and shows at the same time. It covers and uncovers.

If, for someone like Marx, the material manifestation of any object precedes its encipherment, others might submit, instead, that the cipher operates as the occasion for materialization to first take place. Mediation comes first, and materializes the body, someone like Judith Butler would argue. Following such accounts of the performative nature of subjection, one may suggest that the very materiality of the body is a product of a process that relies on cultural, linguistic, affective, and discursive, ciphers. And if the cipher conditions processes of materialization and subjectivation, one can ask if there is anything that escapes its logic. Is there an excess of meaning that remains neither enciphered, nor decipherable? To trace that excess would be to situate the cipher more precisely. It would be an attempt to recognize ciphers where they are, and to isolate those places where they remain absent.

For the upcoming issue of Diffractions we would like to make the cipher speak. To allow it to be heard, perhaps against its will. To ask where the cipher begins, and what exceeds its limits. In doing so, we aim to connect the cipher to objects, to values, to voices, and to the body. Our goal is to investigate the ways in which these concepts can be made useful for the study of cultural objects. How objects of study might help us to make the cipher speak, and how the cipher might engage these objects in return.

We look forward to receiving proposals of 5.000 to 9.000 words (excluding bibliography) and a short bio of about 150 words by October 31st, 2018 to be submitted at our website: https://diffractions.fch.lisboa.ucp.pt/Series2.

Diffractions also accepts book reviews related to the issue’s topic. If you wish to write a book review, please contact us through the e-mail address below.

We aim to be as accessible as possible in our communication. Should you have any questions, remarks, or suggestions, please do not hesitate to contact us through the following address: info.diffractions@gmail.com.

-

“The Way we Work Now”: Irit Rogoff at Universidade Católica

Irit Rogoff’s lecture “The Way we Work Now”

Diffractions Lecture Series on “Creative Knowledge Practices”, with CECC and Lisbon Consortium

Lisbon, October 12 2016